NAVIGATE THROUGH THIS HOMEPAGE

(click to go to each section)

INTRODUCTION

POLITICAL DOCUMENT

Safeguarding the Right to Education in New Forms of Global Governance and in the Digital Age:

a Call for Action Against Privatization[1]

It’s been a long time, education is no longer confined to the borders of a nation-state; it has evolved into an international endeavor. In this global context, with a growing variety of decision-making spaces and actors, the influence of the private sector on the governance of education threatens more and more the fundamental right to education worldwide. In the contemporary political and economic landscape, we must also recognize that capitalism is inherently tied to issues of colonialism. Consequently, the prevailing neoliberal policies in the XXI century have ushered in a period of reduced government spending, deregulation, and widespread privatization, especially in the Global South.

Within the education sector, privatization represents a fundamental shift in responsibilities, as the state relinquishes its role as the primary provider of equitable, high-quality education, ceding space to the private sector in the provision and management of education, threatening the supply and quality, and increasing the profits of multinational companies headquartered in wealthy countries. This brand of education is designed to perpetuate a cycle of subordination rather than providing an empowering human right.

Over the past two decades, a shift towards multistakeholderism has raised concerns about the privatization and commodification of education, sidelining the centrality of the nation-state in global decision-making to the private sector. It often places developing countries in a precarious position, where corporate interests tend to overshadow the public good. To challenge this corporate capture of the multilateral system, it is imperative that developing countries advocate against the growing influence of the private sector in global governance, particularly in the context of education.

This document critically examines the privatization in education in its global governance and calls for political advocacy for a shift towards greater public investment in education with democratic participation and against the influence of the private sector. This advocacy should aim to halt the commodification of fundamental rights, particularly the right to education, which remains under constant threat from such mechanisms.

The Stranglehold of the Global Debt Crisis

The global debt crisis presents a significant constraint on government revenue spending for public services, including education. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) plays a pivotal role in this scenario, exerting substantial influence over countries in debt. The IMF's policy advice and loan conditions often force countries into austerity measures, leading to underfunding of public education. Countries that heavily rely on external cooperation partnerships for education funding are subjected to external demands and conditions that may not align with its long-term development vision.

The IMF's voting structure, established in 1947, perpetuates neocolonial power dynamics by giving disproportionate decision-making weight to wealthier countries. This imbalance sustains underfunding of public services and creates opportunities for multinational corporations, primarily from the Global North, to benefit at the expense of developing nations.

In many countries, debt servicing consumes more resources than education. The IMF's austerity policies result in reduced spending on education and block the hiring of public sector workers, including teachers and healthcare workers.

Multistakeholderism and Global Governance

Multistakeholderism, with its focus on diverse stakeholders in decision-making processes, has gained prominence through many aspects and as a response to funding challenges in global governance. However, the capture of these spaces by private sector actors implies a departure from a rights-based agenda in favor of privatization and commodification of rights.

The mechanism lacks clear and democratic selection processes for participants, leading to conflicts of interest and the exclusion of genuinely interested actors. This undemocratic aspect hinders the representation of diverse voices in decision-making. Power imbalances, mirroring colonial dynamics, persist in these spaces, with the Global North largely prevailing over the Global South.

Since 2015, various initiatives have emerged, predominantly influenced by the corporate sector and a recurring issue is the presence of similar actors and personalities across multiple instances, contributing to the blurring of lines between state and non-state actors. The private sector's influence extends to UN agencies complicating the analysis of their participation in global governance considering that the interests of the private sector are defended beyond their official representatives in these spaces.

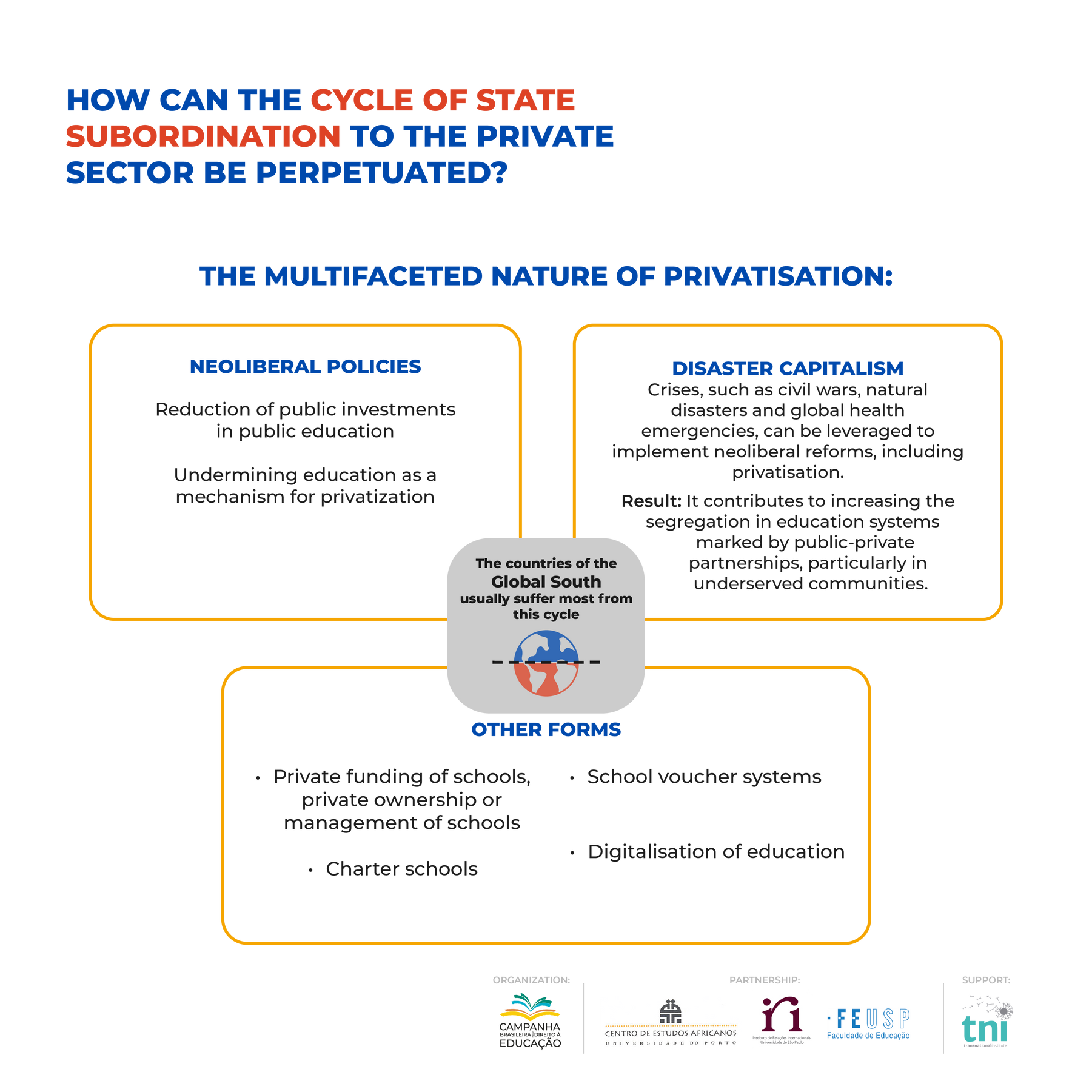

The Multifaceted Nature of Privatization

The problem of privatization is not confined to specific countries; it is a global issue. Across the world, public-private partnerships fail to improve learning outcomes and exacerbate disparities. Research shows that privatization negatively impacts equity in education and this right fulfillment.

Key organizations operate at various levels, from local to international, shaping the privatization discourse. The influence of these organizations transcends borders, and they often engage in conversations that exclude the voices of local communities.

Even in countries where the law guarantees free education, it lacks proper regulation and there are economic barriers that prevent poor students from accessing it, such as transport, food and book fees. In Chile, textbook publishers have played a significant role since the 1980s as they exert substantial control over educational materials.

During the pandemic, the relationship between publishers and tech giants like Microsoft was reinforced, exacerbating existing disparities in the education system.

Disguised privatization, or endogenous privatization, involves introducing a private-sector culture into the public education system. In Chile, this phenomenon gained momentum during post-dictatorial governments, particularly between 2006 and 2011, responding to student mobilization. Private actors have been involved in shaping regulations, funding models, and management structures, ultimately influencing the education landscape. Until nowadays, Chile's constitution lacks a guarantee of the right to education. This omission permits the expulsion of students and dismissal of teachers without violating constitutional rights, as the prevailing principle is the freedom of teaching.

The World Bank plays a pivotal role in shaping global education policies through its education advisory group, inviting significant investors and large corporations to invest in educational projects. This is not mere philanthropy but an investment with financial returns, often leading to debt burdens for developing nations.

Disaster capitalism, where crises, such as civil wars, natural disasters and global health emergencies, are leveraged to implement neoliberal reforms, including privatization, contribute to increasing the segregation in education systems marked by public-private partnerships, particularly in underserved communities. School selection and student exclusion become pronounced issues, perpetuating inequities.

Privatization in education is not confined to a single approach or avenue but manifests in diverse forms. These encompass private funding of schools, private ownership or management of schools, low-cost private school mechanisms, charter schools, and school voucher systems. Today, new forms of governance and digitalization of education serves as a significant gateway for privatization

The Impact of Neglected Governance and digitalization

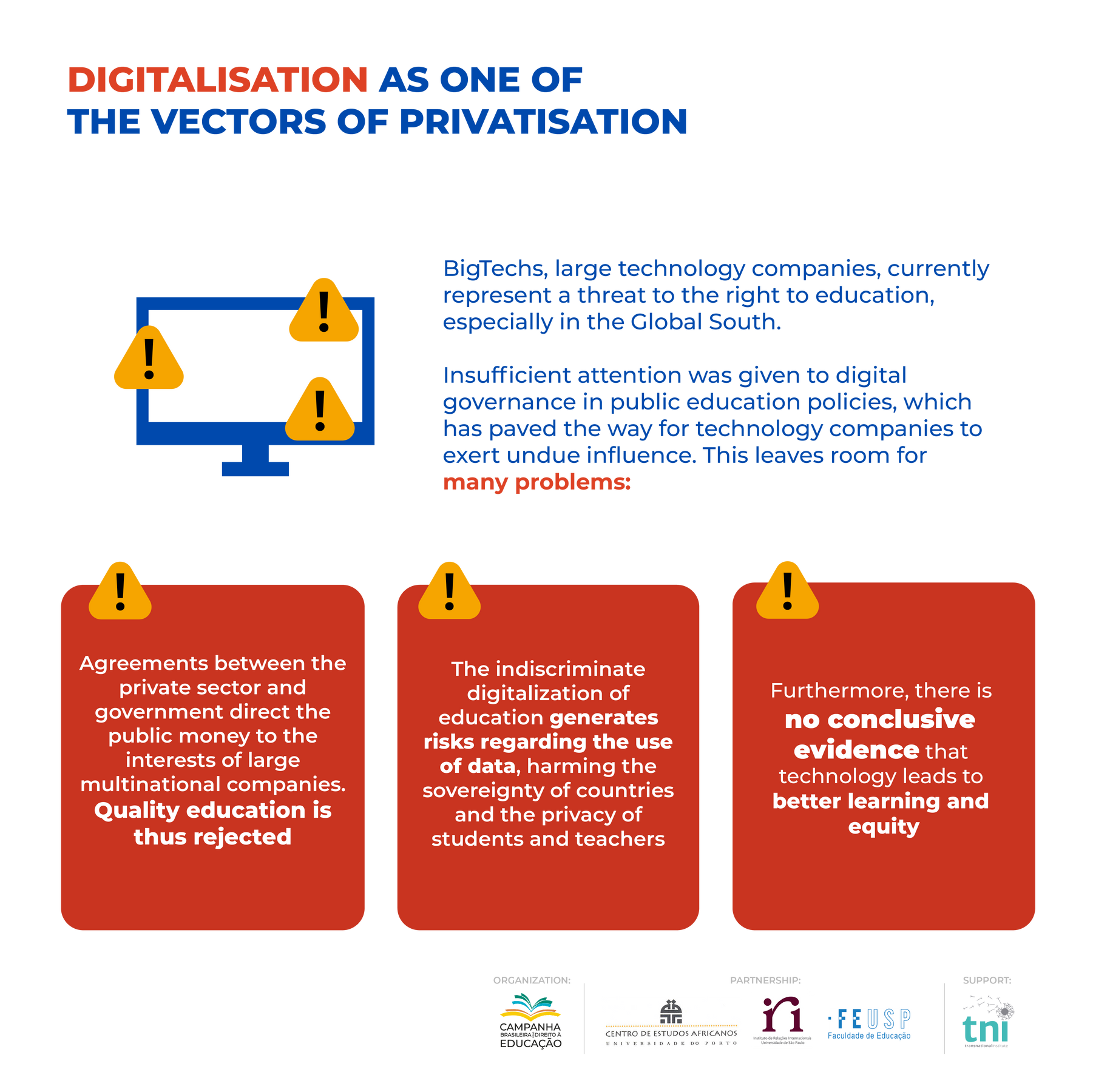

Chronic underfunding of public education has created space for aggressive privatization and commodification, particularly through digitalization. This trend further endangers equitable access to quality education.

Insufficient attention was given to digital governance in public education policies, which has paved the way for technology companies to exert undue influence. The 2023 GEM Report by UNESCO emphasizes the need for governments to consider why and how technology is used in education and evaluate its true benefits.

The rise of digitalization in education has brought about new challenges that demand attention. While the internet was once seen as a tool for democratizing information, it has now become a space where users must accept complex terms and conditions, eroding the notion of free access to information.

The proliferation of technology in education is not merely about allowing or prohibiting the use of devices like cell phones in schools. It entails understanding the broader implications, such as data privacy risks associated with artificial intelligence and platforms used in educational applications. Moreover, there is no conclusive evidence that technology leads to improved learning and equity.

The emergence of start-up companies offering educational applications via mobile phones, often in partnership with major tech corporations from Global North – the known Big Techs -, marks a concerning trend. This process parallels a form of digital colonization, where companies exploit the accessibility of technology among children and adolescents for profit.

Transnational technology corporations are pushing a profit-driven approach to education, primarily in developing countries. Agreements between governments and these companies divert financial resources away from safeguarding the right to education. Instead, funds are channeled into the pockets of technology giants with little regard for educational quality.

Education systems have increasingly outsourced data infrastructure to private companies, compromising data sovereignty and privacy. In Brazil, it was discovered that most educational packages used in 2022 did not comply with the General Data Protection Law (LGPD) or mention it, indicating an acceptance of legal violations.

Impact on Marginalized Populations

The education crisis, particularly acute in sub-Saharan Africa and rural and remote areas worldwide, is exacerbated by the digital divide. Millions of children lack access to education, and the quality of education is compromised. Efforts to bridge this divide often involve entering contracts with EdTech companies that prioritize profit over education, bringing more layers to the crisis.

Marginalized populations in Africa, like in Togo and Mozambique, face multiple challenges in accessing digital education, from a lack of electricity and equipment to parental illiteracy. Girls are disproportionately affected, with increased risks of never returning to school and being forced into child marriage.

In the Middle-East and Asia-Pacific regions, economic impacts of COVID-19 are compounded by wars, conflicts, and political transitions. Rising indebtedness threatens the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), especially in the wake of the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed a lack of global solidarity, rampant corporate greed, and significant educational challenges. It underscored the need for alternative global governance led by collective actors dedicated to social justice and quality public services. Building a strong alliance encompassing student organizations, unions, civil society, and governments committed to policies that preserve education as a public good and a fundamental human right is paramount. Such solidarity can help counter privatization and detrimental digitalization trends.

A Response Based on Human Rights and Tax Justice

In response to the privatization of education, it is crucial to assert the human right to education, as enshrined in the Principles of Abidjan and international treaty laws. These principles underscore key tenets, including equality, non-discrimination, free and quality public education, the humanistic nature of public education, and respect for national standards and processes. Upholding these principles is paramount in resisting privatization.

Education workers worldwide are combating the precarization of their profession caused by privatization. They demand fair compensation, adequate initial and continuous training, and a professional career plan. The appreciation of education professionals is essential to counter the commodification and commercialization of education. Companies offering education at meager prices cannot provide quality education. Unfortunately, unions opposing such practices often face persecution and threats.

Competing for budget allocations against other essential sectors like health, water, energy, and agriculture undermines efforts to combat education privatization. Instead, education movements should collaborate to expand the budgetary "pie" for all public services, fostering equitable development.

Increasing tax revenue through progressive taxation targeting the wealthiest individuals and corporations can transform education financing. Raising the tax-to-GDP ratio by just five percentage points could generate billions annually for public service investments, including education.

Therefore, investment should prioritize the most marginalized communities and students. The farther a child is from urban centers, the more challenging it becomes to access education. If poverty prevails in the country, it is also common for parents to prioritize income-generating activities for their children, postponing their education. This is the case in regions with mining activities in Mozambique where children quit school and engage in artisanal mining as they may find gold.

Resisting Profit-Driven Digitization

The rapid, profit-driven digitization of education is a concerning trend that must be resisted. Instead of embracing simplistic, low-cost digital solutions, we should explore alternative measures considering factors like cost, context, coverage, co-creation, civic space, and cyber security. Publicly funded and managed education with a focus on equity, gender inclusion, and sustainability should be the goal. Social control over government contracts with technology companies and good regulation are essential paths, and students, families, communities, schools, and universities should actively participate in negotiations.

While technology has a role to play in education, it cannot replace the vital interaction between teachers and students. Schools should be viewed as spaces for individuals to develop intellectually and socially. The intersection of teacher and student knowledge is where significant social skills for learning are cultivated. Thus, we must prioritize the human aspect of education over profit-driven digitization.

Monitoring government commitments and employing evidence-based advocacy are critical strategies for promoting the right to education for all. Efforts should also focus on decolonizing education financing, as increased investment through domestic financing can help address structural challenges, including privatization and digitization in Global South countries. Access to information, the preservation of public goods, and the decolonization of education are essential aspects of this endeavor.

Challenging Neoliberalism and Rebuilding the Agenda for Education

Governments must fulfill their obligations to provide high-quality, free public education, necessitating a comprehensive review of laws, policies, and educational plans. Attention should be given to the entire education system, with a focus on global education governance mechanisms, such as multistakeholderism, and including funding mechanisms, school provision, and teacher training, with a focus on non-discrimination. Achieving sustainable and adequate revenue to finance quality, free education requires efficient progressive taxation, the fight against tax evasion, and addressing the issue of national debt.

Neoliberalism, a dominant global ideology intertwined with moral philosophy, has shaped education through a lens of economic utility. It is vital to reassert the right to education. Simultaneously, there is a pressing need to refocus education on state dialogue and responsibility and national development planning, embracing sustainability, social justice, racial justice, gender justice, and economic growth. An education policy led by educators, rooted in educational sciences, and aligned with a national development project can help shift the balance away from profit-driven interests.

To attain fiscal justice, strategic alliances must be forged, bringing together education movements with health, tax justice, debt justice, feminist, and climate justice movements. These broad coalitions can effectively challenge the austerity cult and promote sustainable financing of public services. Investing in public education, teachers, and transparent scrutiny of education budgets is the most effective way to enhance learning outcomes and guarantee education for all.

CONCLUSIONS

The battle against the influence of the private sector on global education governance is a battle for the right to education as a public good and a fundamental human right. To counter this trend, it is crucial to reform global governance, giving states and representative civil society the decision-making centrality, and to address the global debt crisis, reforming global tax rules in a progressive path, increasing tax revenue through progressive taxation, and working collectively to expand the budgetary allocations for all public services.

The influence of the private sector in global education governance poses a serious threat to the right to education and must be fought. This advocacy seeks to raise awareness about the risks associated with multistakeholderism, emphasizing the need to safeguard public education and strengthen democratic processes. It calls for a reevaluation of the current trajectory in global governance to ensure that education remains a fundamental right accessible to all, free from undue privatization and commodification.

This document calls for a united front of civil society, educators, students, and families to resist the encroachment of privatization and the erosion of educational quality. Together, we can ensure that education remains a tool for empowerment, promoting social transformation, justice, and progress on a global scale.

[1] This document was created based on the presentations and reflections made during the International Seminar “Trends in global education: the impact of governance structures, privatization and digitalization”, held in a hybrid manner at the Institute of International Relations of the University of São Paulo (IRI/USP), on September 25th-26th, 2023, in partnership of this Institute with the Brazilian Campaign for the Right to Education, the Centre of African Studies of Porto University (CEAUP), the Faculty of Education of the University of São Paulo (FE/USP), and the Transnational Institute (TNI).

Document’s Coordination and Elaboration

Andressa Pellanda

Helena Rodrigues

See full credits at the end

INFOGRAPHICS

The Brazilian Campaign for the Right to Education has produced infographics so that the discussions held at the International Seminar can be disseminated throughout international civil society on social media.

You can also access the Portuguese and Spanish versions.

SUMMARY OF ORAL PRESENTATION TRANSCRIPTS

Carlota Boto | Director of the Faculty of Education at the University of São Paulo (FE-USP)

Gonzalo Berrón | Friedrich Ebert Foundation Brazil and Transnational Institute (TNI)

Rui da Silva | Center of African Studies of Porto University

Andressa Pellanda | General Coordinator of the Brazilian Campaign for the Right to Education

ROUND TABLE 1 | SCHOLAR’S CONTRIBUTION

Gonzalo Berrón | Multistakeholder Governance: Debates in Several Areas

Frank Adamson | Global Education Reform

Camilla Croso | Multistakeholderism in Global Education Governance

ROUND TABLE 2 | ACTIVISTS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Roberto Leão | Education Workers’ Global Perspective

Marcelo Di Stefano | Threats to Public Services

David Archer | Transforming Education Summit: Next Steps

Priscila Gonsales | Digitalization of Education in Global Governance

Maria Ron Balsera | Threaten to public services

DAY 2 - Civil Society Strategies at the Regional and National Levels

Andressa Pellanda | General Coordinator of the Brazilian Campaign for the Right to Education

Carlota Boto | Director of the Faculty of Education at the University of São Paulo (FE-USP)

Luis Eduardo Murcia | Global Campaign for Education's Policy & Research Advisor

ROUND TABLE 1 | REGIONAL LEVEL

Nelsy Lizarazo | Latin America

Solange Akpo | African Network Campaign for Education for All

Rui da Silva | Portuguese-Speaking Countries

ROUND TABLE 2 | NATIONAL LEVEL

Andressa Pellanda | General Coordinator of the Brazilian Campaign for the Right to Education

DAY 1

Global governance today: challenges, power and privatization between international complexity and digitalization

OPENING REMARKS

The International Seminar on 'Trends in Global Education: the impact of governance structures, privatization and digitalization’ was organized by the Brazilian Campaign for the Right to Education in partnership with the Institute of International Relations at the University of São Paulo (IRI-USP), the Faculty of Education at USP, the Center of African Studies of Porto University (Portugal), and the Transnational Institute (TNI), which also supported the initiative. The event took place on September 25th and 26th, 2023, in a hybrid format at IRI-USP and is available for full viewing on YouTube[1].

Pedro Dallari | Director of the Institute of International Relations at the University of São Paulo (IRI-USP)

There is no sectoral governance that is not also of international dimension. Public policies have become international, management actions in various fields have become international, and for IRI-USP, this evolution is a sign of maturity. We are at a moment that reflects the resurgence of UNESCO's role, which was in a weakened situation in recent years due to a political crisis involving the withdrawal of the United States. This year, the Biden administration announced the country's return to UNESCO. UNESCO, within international relations in the field of education, is a major reference institution. The return of the U.S. to the institution has significant economic and financial components. The United States not only contributes 22% of the organization's annual budget, which has an annual budget of $500 million, but also committed to paying an additional $619 million, which corresponds to the amount that the country did not pay during the period it was disengaged from that organization between 2011 and 2018[2].

In this sense, this is the moment when this major international organization in the field of education revitalizes itself, and therefore, the reflections made in this seminar can directly engage with a more robust and financially capable UNESCO. The role of the university in this regard is crucial because it is the responsibility of the university, in collaboration with governments and civil society, to establish reference frameworks for these public policies that may be produced at the national or even subnational level but increasingly have references in international paradigms.

This brief reflection draws attention to the relevance of this event in a favorable context, at a time of so many crises, at a time of so many difficulties, at least in this area, there is a positive sign that good things can happen in a short period of time, and it is up to us to encourage and promote initiatives so that this actually occurs.

Carlota Boto | Director of the Faculty of Education at the University of São Paulo (FE-USP)

The theme of this seminar, which addresses trends in global education and the impacts of governance structures, privatization, and digitalization, is extremely timely and absolutely current, considering even the headlines in today's newspapers. This is a topic that challenges us and creatively and powerfully connects the studies of the Institute of International Relations with the studies of the Faculty of Education. From the perspective of internationalization, education is now being conceived not only as a project of a national state but as an international project. Therefore, it is of utmost relevance to think about education from the perspective of international relations.

Gonzalo Berrón | Friedrich Ebert Foundation Brazil and Transnational Institute (TNI)

One problem that has been identified in global governance is the various forms of corporate capture of the international system, particularly in a system we call the parallelization of states through multistakeholder mechanisms, which includes actors from the private sector and philanthropic institutions, in addition to civil society, in decision-making processes. This phenomenon is a result of the increasing presence of the private sector in global governance.

The Education sector has a long history in this discussion, and we have observed a deepening of this problem with the shift from a multi-actor system to a system that includes economic interests in decision-making. It is essential that this debate involves activists for the right to education, unionists in the field, teachers, students, and researchers to try to find solutions that place the right to education at the center of public policies, along with strengthening the democratic system.

Rui da Silva | Center of African Studies of Porto University

The theme of this seminar is highly relevant today. As an example, in a recent international conference, there was a presentation on a South-South program by the Lemann Foundation, where educators from Kenya and Pakistan came to Brazil to learn about the Foundation's experience in the country. Therefore, it is increasingly important in this field of study, where there are different perspectives, to also consider opposing movements. The tendency is to focus only on the transfers and influences that the North exerts on the Global South. However, it is also important to identify these South-South movements. In this conjunction of academic work, activism, and civil society, everyone benefits from the collaboration and daily studies that bring various perspectives, advancing knowledge and activist work.

Andressa Pellanda | General Coordinator of the Brazilian Campaign for the Right to Education

This seminar brings together various academic researchers who are also activists for the right to education. This is very important for the Global Campaign for Education, the Brazilian Campaign for the Right to Education, and all education-related networks. This conjunction occurs naturally because there are many research collaborations involving activists and researchers, as well as various partnerships and joint advocacy work at both the national and international levels.

The theme of multistakeholderism is something that has already been studied by the Global Campaign, and the Brazilian Campaign for the Right to Education also discusses it. In dialogue with Rui da Silva and Gonzalo Berrón, we organized this seminar with the Faculty of Education, which has extensive research on all the topics we are addressing today.

An example of the relevance and pertinence of the theme of this seminar can be seen in an article published today by O Estado de S. Paulo newspaper about the influence of private actors in education, especially in the digitalization agenda, as the Escolas Conectadas program will be launched by President Lula himself this week, and the civil society chair will be occupied by an organization related to the private sector [Lemann Foundation][3]. The Brazilian Campaign for the Right to Education, which had already been monitoring this process, informed the journalist who conducted the investigation and published the exposé today.

The Technology Fund has a budget of R$6.6 billion, and its governance includes only companies or organizations connected to companies as representatives of civil society. The Campaign requested by official letter to all the Ministries that make up this group to integrate the working group as civil society, but we were denied. This is not mentioned in the article due to concerns about the exposure of our work.

The influence of the private sector and the privatization of education, especially through the digitalization of education, is a very important topic for which we do not yet have much scientific evidence because it is currently emerging. The purpose of this seminar is to present what we already have and produce more at this moment.

ROUND TABLE 1 | SCHOLAR’S CONTRIBUTION

Gonzalo Berrón | Multistakeholder Governance: Debates in Several Areas

The term multistakeholderismo is a Portuguese adaptation of the term multistakeholderism, which originated in business sciences. Simplistically, the term refers to the inclusion of multiple stakeholders in a government or decision-making structures on a particular topic. Stakeholders are those with an interest in a specific issue, originally referring to economically interested parties within the business market mechanisms. The term has been adopted for mechanisms of dialogue or participation. In recent years, instead of using the term "civil society" to refer to non-state actors within decision-making systems, we have seen the increasing use of the term multistakeholder to represent non-governmental stakeholders.

This is not new; the process has been ongoing for over 20 years and is purportedly a response to a funding problem. In this sense, global governance would have given up on making decisions on some areas and guiding its actions according to a rights agenda in favor of an agenda that leans toward privatization and the commodification of services due to a lack of monetary resources. This is the response we have received from the international UN system. Therefore, various formulas were invented in the name of the international system's lack of resources, one of which is the growing evolution toward multi stakeholder mechanisms.

An important moment in this process occurred after the global crisis of 2008, at a time when the multilateral system, which was already in decline and needed private sector funding to supposedly address fundamental agenda issues, failed to resolve a predominantly global crisis, the financial crisis. Later on, we will see that failure has occurred in several other crises, and in every crisis, the response has been to strengthen the role of the private sector in governance. However, the private sector also fails in solving this problem, and perhaps it is itself the problem in global governance.

So, in 2008, with the global economic crisis, among other crises but focusing on the economic crisis, the World Economic Forum gave new status to multistakeholderism and initiated a global debate process called Global Redesign Initiative. It was a process that mobilized hundreds of researchers and opinion leaders from around the world, all within the context of the World Economic Forum. The result was the Global Redesign Initiative, which proposed a redesign of global governance with a focus on bringing multistakeholderism, a mechanism in which the private sector is part of decision-making, to the center of the World Economic Forum.

It was from that moment that we began to take this threat seriously, but we arrived late because this process was already strongly driven at the UN level and in other areas. Civil society then began to understand that it was not just a failure or a problem in a specific area of global governance but in all areas. As the multilateral system was being drained of funding, especially, the demand for providing services and solutions at the global level was growing, and it was clear that these two things needed a more systemic approach.

From there, the term multistakeholderism was consolidated and mentioned in various speeches, including by UN officials, and was spoken of both positively and as a common-sense aspect of global governance. This naturalization of a form of governance not only biases governance mechanisms but also the public policies that emerge in the international system.

The next step in this process occurred through a partnership proposed between the World Economic Forum and UN Secretary-General’s Guterres. In 2019, they signed a partnership agreement between the UN Secretariat and the World Economic Forum for the strengthening of global governance and the multilateral system. This is a significant threat as it represents the entry and access of technical experts from the World Economic Forum to the multilateral system. The terms of the agreement are somewhat vague but essentially permit access to the system and propose the best solutions for global governance challenges. The rhetoric, in general, is very positive but, in reality, hides the true problem, which is how rights are being transformed into commodities and how the entire range of public services that are rights are turning into commodities.

Behind this process of commodifying rights are the major global mechanisms that encourage and drive this transformation.

Systemic contestation of multistakeholderism began with the denunciation of this agreement, which was signed by over 400 civil society organizations. This moment was important because it initiated the coordination of various central sectors, primarily from a rights perspective, particularly in global governance, that were impacted by multistakeholderism. A comprehensive mapping was done on education, environment, food and agriculture, health, and the digital world, which today is almost a basic necessity. This mapping was collaboratively conducted between academics and activists and resulted in a massive book that maps these mechanisms up to 2020.

The book is a significant observation of the phenomenon, showing how areas of global governance, such as health and education, have dozens of these mechanisms, some of which work and others that do not. But the issue is that there is a normalization of this type of arrangement, which represents a failure in one aspect of the multilateral system.

The UN Secretary-General launched the "Common Agenda" document two years ago to discuss global governance, in part because they know what the problems are, that countries do not contribute the needed funds, and that they must turn to the private sector. The document describes the characteristics of global governance and the multilateral system in the coming years.

And it seems that the world's solution is coming with the creation of 18 more multistakeholder mechanisms, which suggests a solution to public problems through the participation of the private sector and private interests. Within this perspective, institutions that will issue decisions or recommendations, and no one knows who they are or how they function, are included. In fact, there is no accountability, no description of procedures, nothing. And, in fact, they later become working programs of the UN or some prominent mechanism.

This kind of mechanism is a problem not only for civil society in terms of rights but also a problem in terms of decision-making for states, especially for developing states, which barely participate in multi stakeholder mechanisms.

Multistakeholderism puts developing countries in an uncomfortable and marginal position. If developing countries understand multistakeholderism as a corporate capture of the multilateral system and reinterpret the use of the term to include its negative consequences beyond solving the funding problem, it will be possible to advocate within global governance systems and reverse the processes of commodifying rights, especially the right to education, which is one of the areas most impacted by this type of mechanism.

Frank Adamson | Global Education Reform

In education, we can observe patterns of neoliberalism at different levels: international level, domestic national levels, and even at the local level, often with little communication among these levels, at least within the public sector or civil society, while they are very present concerning the role of corporate actors or the private sector.

The origin of what I call neoliberalism 1.0 is Friedrich von Hayek, after World War I, when state-sponsored violence in the form of war devastated Europe. He signaled the need to move towards markets because such a level of power couldn't be entrusted to the state.

Next, we have the market-based Great Depression, and Keynesian economics determined that the state should heavily invest with deficits to improve society for the people. Fast forward 40 years, and we arrive at what I call neoliberalism 2.0 when Milton Friedman suggests that instead of just liberalizing the economy, it is necessary to deregulate and privatize.

So, we have this general political and economic approach nowadays, the racialized free-market capitalism. In 2023, I won't use the word capitalism without involving the racial question because they are interconnected. There's a reduction in government spending, as I mentioned, deregulation, and privatization. In the Education sector, privatization can be basically defined as the transfer of the state's responsibility to provide equitable and high-quality education to the non-state sector in various ways, relegating the state to a subsidiary role. The private sector and the market become the primary providers.

It's not just about following the money. Privatization can occur in many different ways. It can be private funding of schools, but it can also be who owns or manages the schools. Most people think that if it's publicly funded, it's public, and that simply isn't true. Privatization takes place in many different places and through various avenues, whether it's through low-cost private school mechanisms, charter schools, or school vouchers.

But the process of education privatization hasn't always been so diversified. In the 1970s, Augusto Pinochet enacted Milton Friedman's neoliberal version, privatizing education and the economy in Chile. Meanwhile, in Finland, there was a focus on educational equity. They have very different outcomes. A generation later, we saw the contestation in Chile, which continues to this day, with attempts to modify the Constitution. And then we have Finland, which has been leading in international assessments.

These are very different approaches that we examine in the book 'Global Education Reform[4]'. Instead of making a direct comparison, we compare Chile with Cuba, another Latin American country; the USA with Canada; and Finland with Sweden.

In Chile, we see the neoliberal model through school vouchers since the 1980s, fundamentally altering the funding and structure of the system. In 2018, 60% of students were enrolled in private schools. In Cuba, you have a very different system, with centralized control, command economy, and what we call state-driven social capital, with robust social programs and general wage equality in all sectors, including teachers, who are closely supervised and trained. And you have very different outcomes. Although Cuba doesn't participate in many exams, we see that its results are very different from Chile's. Cuba is actually outperforming many other countries. This is what's happening in the Latin American context.

The United States is a source of global ideological reproduction, but it is also a place where these things happen, and, in particular, the mechanism of public-private partnerships in the USA is charter schools, which receive government funding but operate independently of the state school network. In the United States, we have a highly segregated education system, where the focus of public-private partnerships has been on poor and black communities, especially New Orleans, where almost all schools are public-private partnerships in the form of charter schools.

4 Adamson, F.; Astrand, B.; Darling-Hammond, L. (2016) Global Education Reform: How Privatization and Public Investment Influence Education Outcomes. Routledge

Naomi Klein calls this disaster capitalism, where disaster is an opportunity for taking control and implementing neoliberal reforms, especially privatization. It's important to note that the framework for taking over New Orleans was established before Hurricane Katrina. This is due to George W. Bush, who took the presidency in the United States, rewrote education law to include the idea of failing schools and their transformation. Neoliberalism was institutionalized, and Katrina became the opportunity to fire teachers, mainly Black teachers, 7,000 without due process, and replace the schools. And you end up with a tiered system of schools that select students. When we talk about equity and privatization, one of the biggest problems is school selection, student exclusion.

There are many different mechanisms for this. We see that top-performing schools, Tier 1 schools that literally select students, even though they are "public," have about 90% white students. In these schools, they teach pure knowledge, and they are not obsessed with testing. On the other hand, alternative schools, where the non-selected children are directed, have about 76% African American students. These schools claim to be providing remediation, with children's experiences narrowly focused on basic test skills. In Tier 3 schools, students spend the entire day on the computer, with radically different pedagogical approaches within the same city and schools located just a few blocks apart.

In other words, in the United States, we have massive segregation. We see that charter schools are really focused on African American students. Segregation is a problem across the spectrum. However, what happens in urban schools is that African American students end up attending intensely segregated schools, with 90% of students in poverty and/or African American.

The private sector, which promises to address the situation, is actually exacerbating the problem, especially for African American students and those with special needs. This is not just happening in the United States or Chile. We have analyses showing that this is a problem worldwide, and public-private partnerships are not really improving learning outcomes. Tony Verger and his co-authors examined 199 studies and found that equity was a negative issue in all the different schools with public-private partnerships[5].

When we look at the international network map, we can see that some organizations operate in various locations[6]. When we turn to the United States, we can see that some of these same organizations also operate at the national and local levels[7]. In this way, we can observe these different instances of neoliberal ideology occurring at different levels, and these groups are in conversation with each other, sometimes being the same groups: the Gates Foundation, Teach for America, now called Teach for All, and KIPP (Knowledge Is Power Program), which operates on all three levels on all these maps. And certainly, families in Oakland do not have a voice at the international level in the same way that KIPP does.

KIPP focuses on low-income students, which is great, and they are extending the school day. However, they have a zero-tolerance policy, which means they give suspensions and expulsions for behavioral issues. They use a process called 'SLANT, (Sit up, Listen, Ask and answer questions, Nod, and Track the speaker), which is a behavioral tracking. Students who do not follow the teacher's gaze can receive a warning that leads to suspension. Therefore, the effectiveness of their results is contested because it is tied to student selection and exclusion.

The response to the processes of education privatization is based on the fact that there is a human right to education, articulated in the Principles of Abidjan[8] and throughout the United Nations and other treaty laws. The principles are equality, non-discrimination, free and quality public education, the humanistic nature of public education, respect for national standards and processes. We should not fall short of this threshold. We have a lot of work in different networks in this regard. We have the Principles of Abidjan book, where we present all cases of human rights. We have 'Public Education Works'[9], where we describe systems, especially in the Global South, that are working. I work with communities in Oakland, and I think most people in Oakland are unaware that São Paulo had school occupations to prevent them from being closed, just as most people in São Paulo probably do not know that Oakland is also facing large-scale closures based on these efficiency ideas that are part of the neoliberal movement. And from a network perspective, there are networks working at a global level, such as PEHRC (Global Campaign on Privatization of Education and Human Rights), the Brazilian Campaign for the Right to Education, among others.

Camilla Croso | Multistakeholderism in Global Education Governance

The work presented here was done in partnership with Ruy da Silva and Giovanna Mode and deals precisely with the phenomenon of multisectoral governance, or multistakeholderism, in the context of global education governance and the problems that arise in terms of democracy as this is also a business for the private sector, generating profits. Multistakeholderism is a phenomenon that has been very little studied in education, which is why it is very necessary to delve into this topic.

This work aims to delve into the issue of education privatization. The privatization of governance itself, of political action, is a topic of fundamental importance to us. Therefore, the relationship with the private sector and how it participates in the decision-making process seemed absolutely crucial. We chose to look at three instances of multistakeholderism at the global level.

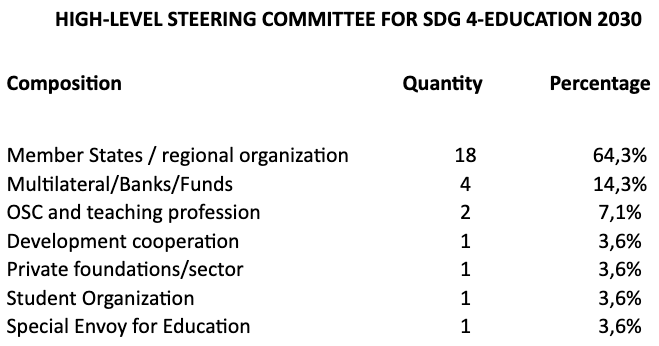

The High-Level Steering Committee of SDG-4, which is the main instance of global education policy where the content of SDG-4 was negotiated and approved along with the other 16 SDGs, as well as the details of SDG-4, where we were able to detail other fundamental elements, such as the provision of free education and various other principles.

Another instance that we would like to analyze in more detail is the Global Partnership for Education because it is also an instance of great influence. The High-Level Steering Committee has been in existence since 2000 and has changed names, but fundamentally, it comes from the Dakar Forum. The Global Partnership for Education also dates back to 2002 when it was initiated under a different name.

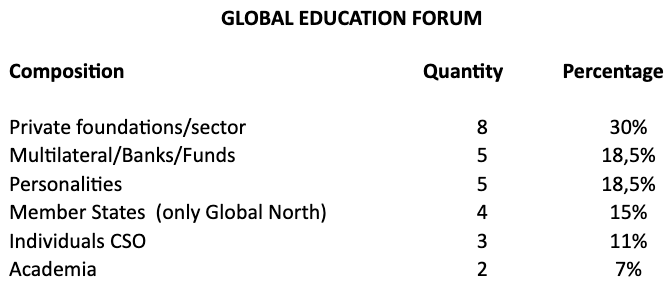

A third instance of interest is the Global Education Forum, which is much more recent, with particularities that clearly represent the issue of multistakeholderism in the field of education.

The idea of multistakeholderism refers to the governance of multiple stakeholders. The term is used because states, which have the predominant role in decision-making in multilateralism, have their relevance diluted with the incorporation of various other actors in decision-making, such as the corporate sector, private foundations, and civil society; this last one was already present in multilateralism. It is a mechanism that repositions the centrality of the state in public policy.

The World Economic Forum played a fundamental role in consolidating this perspective of multistakeholderism, even though this concept dates back to well before, to the Rio '92 (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development), where what are now called major groups and stakeholders were born, which is a mechanism that emerged at that time and has become a dialogue instance for civil society and other stakeholders.

However, it is the Davos Forum that truly consolidates the concept of multistakeholderism at the global level in 2010. The Global Redesign Initiative formally calls for a new global governance and states that it is time for the stakeholder paradigm to be the guiding paradigm of global governance in the context of what is referred to as stakeholder capitalism.

The Davos Forum states that this new form of governance involves voluntarism and decision-making processes by multiple stakeholders that should take precedence over the authority of the nation-state. For the social field to better understand what Davos meant in terms of education policies and these dynamics is a very important step for advocacy actions for the right to education.

Gleckman[10] offers extensive reflections on the multistakeholderism phenomenon and highlights some fundamental elements, such as how the selection of participants who comprise these governance instances is carried out. There is no clear democratic or rational process that determines who gets in and who doesn't, leading to a problematic conflict of interests with individuals genuinely interested but excluded from the discussion space.

Gleckman emphasizes another very interesting element, which is the role of secretariats of organizations within multistakeholderism and within UN agencies, and how these secretariats take precedence vis-à-vis the base, which are the states in multilateralism. This became clear during the negotiations for SDG 4, as it was very tense because the secretariat had much more information than the states, and there was a total lack of dialogue. Furthermore, one can observe how the secretariat smoothly handled the entire debate, leading the discussion, and the states were held hostage due to the lack of information circulation.

Another aspect that Gleckman brings up is the power asymmetry among different stakeholders. For example, transnational corporations start to occupy spaces alongside donor countries. A power distribution logic between North and South based on resource issues.

Additionally, Manahan and Kumar address the issue of epistemic communities that are self-referential and generate networks with the same actors who use different names and attire but are always the same[11]. In this way, they organize themselves and exist in different spaces, allowing them to have significant power because they are present in all spaces of information and decision-making circulation.

The SDG 4 Steering Committee is now part of what has recently been called a global cooperation mechanism. In this space, various other actors engage with the Steering Committee, such as the youth network, the multilateral educational platform, the inter-agency secretariat, the Global Education Forum, and NGOs. Within this mechanism, the same actors who participate in various other platforms achieve greater relevance precisely because they are simultaneously involved in multiple spaces.

The SDG 4 Steering Committee, hosted by UNESCO, is the main governance body, and it is the instance in which civil society has been able to participate in a much more systemic and organic way since its creation around the year 2000. From the beginning, civil society's demand has been for multilateralism to be a fundamental principle of this space to ensure the primacy of states, accompanied by civil society, education workers, and students, who only recently joined. Recently, this space has begun to define itself as multistakeholder.

Regarding its composition, the Steering Committee has a prevalence of states chosen equitably, with three countries per world region. There is very high participation from other UN agencies, such as UNICEF and UNDP, banks, and the Global Partnership for Education (GPE), and then others in much smaller numbers, such as civil society and the teaching profession. The private sector itself has a chair shared with foundations, and the special envoy for education is present. Recently, students have been incorporated.

Unlike the Steering Committee, the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) has always had a much narrower focus since the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000. They reduced the education agenda solely to the issue of access to primary education and gender equity in terms of access to the primary system. So, the agenda is already seen as much more restricted. It is headquartered in Washington, at the World Bank, which speaks volumes about the power that the bank wields in this space. Another particularity is its local-level operations, with local education groups primarily funded by the World Bank and UNICEF. This alliance coordinates 79 countries in the Global South and 20 donor countries and operates on a North-South logic. The GPE has donor and recipient countries, as well as dividing civil society into North and South.

In terms of composition, the GPE has four types of actors, with a prevalence of states, 12 donors, and 12 recipients. Since we have many more developing countries in practice, proportionally, the global north prevails to a much greater extent.

The Global Education Forum, on the other hand, is more recent, having started in September 2019. It was one of several initiatives by the United Nations Special Envoy for Global Education, Gordon Brown, who served as the Prime Minister of Great Britain and is a key figure in comprehending the entire global governance of education on an international scale. The prevalence in this space consists of private sector organizations, private foundations, individuals, and multilateral organizations. Governments serve solely as donors, specifically from Global North countries. The participation criteria are unclear, and there is an overlap of actors who participate in other global spaces.

In the Global Education Forum, there is no prevalence of states. What prevails are private foundations and the private sector, followed by multilateral organizations. Member states are exclusively from the Global North, and there are individuals who are prominent figures.

Initially, we had the Steering Committee for SDG 4, which began in the year 2000, and the Global Partnership for Education, which also started in the 2000s. Then, in 2012, the Global Business Coalition was created, chaired by Gordon Brown's wife. Subsequently, following the approval of SDG 4 in 2015, there has been a proliferation of many other spaces, such as Education Cannot Wait, a fund for countries in emergencies founded by Gordon Brown, and the Education Commission, established in 2016, also by Gordon Brown, with a lending mechanism as part of a coalition of banks that has been discussed since 2016 but was formally launched only in 2022 by the UN Secretary-General. We also have the Education Outcome Fund, created by Gordon Brown, which is an investment fund where there is a return rate if students perform well.

In summary, there has been a proliferation of these spaces since 2015, with a significant prevalence of the corporate sector. It's important to note that the private sector also occupies positions within UN agencies like UNESCO and UNICEF. This means that when analyzing these instances of participation in global governance, it's necessary to consider other aspects beyond just identifying who occupies the chair, as the private sector employs various strategies to influence decision-making, and this has been happening with much more emphasis since 2015, to a much greater extent. States, fundamentally, have been sidelined in more recent formations.

Another observed phenomenon is the increasing presence of individuals, personalities, who now occupy these multi-stakeholder spaces. In addition to private sector organizations, we now also have the presence of individuals. It's indeed an extreme atomization.

Another critical issue is the colonialism evident in the power imbalance between countries of the Global North and South in these spaces. With the exception of the Steering Committee for SDG 4, which aims to invite an equal number of countries from each world region, in other spaces, the Global North prevails, with a notable example being the Global Partnership for Education, which operates on a North-South logic in both its engagement with states and civil society.

A third point of concern is the presence of similar actors and personalities across various instances. This logic of personality, closely tied to entrepreneurship, is increasingly prevalent. These actors participate in multiple spaces simultaneously, in an ambiguous and often undefined relationship between where the state begins and ends.

The concept of multi-stakeholderism has become normalized but has been insufficiently scrutinized. While the term may sound democratic, what is actually observed is a radical reduction in the role of the state, accompanied by blurred relations among the actors within the structure and the way these actors adopt multiple identities. Therefore, it is not sufficient to analyze the influence of the private sector solely by identifying the official positions it holds within decision-making bodies.

ROUND TABLE 2 | ACTIVISTS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Roberto Leão | Education Workers’ Global Perspective

Education International has 32 million members in 170 countries, with approximately 400 affiliated organizations worldwide. We are a large, union-based entity that organizes education workers from all over the world who deal with people in all their differences, virtues, and the diverse cultures of the world. Some say that we only engage in corporate struggle, defending our corporate interests, but we have a history of advocating for public education.

We understand that education is fundamental for a country's development, and in our view, it should be developed with the needs of the population in mind, committed to the well-being of individuals, in the spirit of Paulo Freire. It's an education that isn't about conditioning or training; it's about liberation and enabling people to understand and change the world. While some may perceive our demands as primarily for salary increases, which are important, we will never cease advocating for better living and working conditions, salaries, democratic management, and more.

Since 2011, we've observed a global strengthening of movements toward the privatization and commodification of education, which we've also seen in Brazil. We've been engaged in a worldwide battle to ensure that public education receives the funds, investments, and public resources it needs, rather than being appropriated by those seeking profit.

Increasingly, we've noticed how global governance bodies have been co-opted to favor the interests of institutions like the World Bank and the IMF. UNESCO, in particular, is not what we'd like it to be, and the OECD is an organization of entrepreneurs that now organizes an educational assessment test worldwide.

What we see is an attempt to standardize education worldwide, often excluding a model that nurtures basic skills for students. This kind of education has become the only option for those destined to occupy a subordinate role in the world, rather than a position of empowerment. In the case of Brazil, the high school reform has reduced the curriculum for all subjects except Portuguese and Mathematics. The underlying idea is that knowing Portuguese is necessary because workers need to read manuals to operate machinery without errors, and Mathematics is required for basic calculations. Meanwhile, other subjects that teach students to understand the world, such as History, Geography, Philosophy, and Science, are deemed superfluous. This project serves to enrich those who are already wealthy.

The funding provided by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund encroaches upon public funds to practice an education of highly questionable quality, primarily aimed at generating profits for a minority. The World Bank has an education advisory group that invites major investors and large corporations to invest in World Bank education projects. This is not philanthropy of the past but rather an investment with financial returns, often at the expense of indebting developing countries. An example is Bridge International, a British company that operates low-cost schools in Uganda, providing education for $6 per month per child, hiring untrained teachers, and earning $10 per month per child.

Education workers fight against this kind of education precarization caused by privatization, demanding the valorization of education professionals, including initial training and a professional career plan. Professional appreciation is essential, as is ensuring the end of the commodification and commercialization of education. A company that offers education at $6 per month per student knows exactly what it is doing and cannot provide any quality. Unfortunately, in Uganda, unions that oppose this are persecuted, and their leaders face numerous threats. The same happens in the Philippines, where our Education International representative rarely sleeps in the same place for a week due to security concerns, as he is persecuted by the government for denouncing such policies.

The situation in Brazil is no different. There are places where unions are pushed away from their role, or where union mandates are denied, and union members are threatened with dismissal. The state of Mato Grosso eliminated paycheck deductions, which were used for union contributions. They forced the union to re-register all members at a bank. The problem is that some banks do not process these registrations or charge exorbitant fees for doing so. These are just some examples of the various ways in which the trade union movement is persecuted.

Despite these challenges, the trade union movement continues to fight for public education. We saw the news in the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo today about the Lemann Foundation. On January 12th of this year, we reported this and issued a public statement stating that the Ministry of Education was dominated by corporate foundations. Today, we are witnessing this happening in practice. They use the justification that it is voluntary work to gain a foothold in a space that facilitates access to public funds.

In Latin America, we have a Latin American pedagogical movement that fights against the commodification of education and advocates for a pedagogy that considers our unique characteristics as a continent influenced by three races: forcibly brought African slaves, indigenous peoples, and Europeans. Our goal is not to exclude anyone but to build a pedagogical model that considers our characteristics rather than the European model that currently dominates education.

Marcelo Di Stefano | Threats to Public Services

The Global Network of Education Support Workers brings together technical and administrative workers, commonly referred to as non-teaching staff, from various countries in our continent. During this morning's union discussions, the focus was on the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly those related to education. However, we also link them to the Sustainable Development Goals, specifically to the eighth point, which addresses decent work.

Our perspective is to ensure that education contributes to social transformation and that workers have decent wages, stable jobs, and working conditions that enable the exercise of their labor and union rights. Therefore, we place this discussion in the context of commodification, considering the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the digital revolution, the impact of the Internet, and robotics on the world of work and education.

From a union perspective, we question whether the Fourth Industrial Revolution will require more or less human labor than the previous one. We know there are ongoing debates on this topic, reflecting changes from previous revolutions. However, there is a consensus that this revolution will not demand the same jobs as before. Therefore, education plays a crucial role in preparing workers for these changes.

We also wonder if the same political and legal tools will be effective in protecting workers and how this relates to education. In this regard, the International Labor Organization (ILO) conducted an important debate and established a commission to develop guidelines on the future of work. This commission arrived at an interesting diagnosis of inequality in society and the need for decisive action to address it.

This led us to emphasize the need for massive investment in social capital, worker training, and the education of our children and adolescents. We also emphasize the importance of social protection. Statistics on inequality are alarming, particularly concerning poverty, women, the LGBT community, indigenous peoples, and people of African descent.

Moreover, the pandemic revealed a lack of solidarity, corporate greed, and challenges in education. We need a different global governance, led by individuals committed to social justice and quality public services.

We must build a strong alliance that includes student organizations, unions, civil society, and governments committed to our policies. We must defend education as a public and social good, a fundamental human right guaranteed by the state, amidst threats of privatization and harmful digitalization. Quality education is essential for social transformation and progress.

We face challenges, but we believe we can create a more democratic and generous global governance, working together to shape a new model of society and education. We must fight against corporate capture of power and the unbridled pursuit of profit. Let us unite in a strategic alliance to transform education and, in turn, transform our societies.

David Archer | Transforming Education Summit: Next Steps

Public education has been chronically underfunded worldwide for the past 40 years, which plays a critical role in creating space for aggressive processes of privatization and commodification. It also contributes to the idea that there is an education crisis, opening the door to various solutions, including these supposed forms of multistakeholder work. I have been involved in global education conferences for a long time. The first one, which many will remember, took place in Jomtien, Thailand, in 1990, known as the World Conference on Education for All, followed by Dakar in 2000 and Incheon in 2015. All these major global education meetings tend to focus massively and disproportionately on the role of aid and loans, as if aid and loans were part of the solution to the education crisis when, in fact, the evidence is very clear that 97% of education funding worldwide comes from domestic sources. Yet, domestic education financing is almost never the focus of discussion at international meetings. When we consider that 97% of funding comes from domestic sources, it gives the impression that national governments are in control of their education financing. However, there are massive distortions both nationally and globally that affect governments' power to secure more funding and transform their education systems.

I have been involved in the development of financial tracking for the UN Transformation Education Summit, which took place in September 2022, a year ago last week, and it was a UN summit. I also engaged in consultations with the 193 UN member states to develop a position and issue a call to action. We very deliberately focused on shifting attention away from the overwhelming emphasis on aid and loans and toward domestic financing and the necessary local and global action to transform it. When people talk about domestic education financing, what they often cling to is the share of the national budget that should be spent on education. There is a well-established reference dating back about 20 years, reaffirmed in the Incheon Framework, that governments should spend 15% to 20% of their national budget on education. Our governments fall short of that. But there are even more governments that come close to or chronically exceed the 15% to 20% budgetary spending on education, yet still chronically lack resources to genuinely transform their education systems because it's a 20% slice of a very small budget. However, the global and national education community pays very little attention to what can be done to increase the size of the pie, so that a 20% slice of that pie becomes significant.

The forces affecting the overall size of the pie have implications not only for education but for all other public services. One problem we face is that, in trying to advocate for education spending and fight for a larger share of the budget for education, we end up competing with the health, water, energy, or agriculture sectors because we are competing for a slice of the pie rather than working together with other public services to increase the size of the pie, benefiting everyone. This has become a very active debate created by international manipulation to focus civil society solely on the budget slice that concerns them and divide forces. However, we will never successfully combat privatization in education if privatization continues aggressively in health, water, and other sectors.

Therefore, if we want to change this, we need to unite collectively and look at the size of the pie. One of the biggest constraints on government revenue spending for public services, currently, is the scale of the global debt crisis. There are already 54 countries in debt crisis, a massive increase in the past 4 or 5 years. Many other countries are at high risk, and the vast majority of countries are at moderate risk.

One consequence of debt is not only that the amount of money available for spending on public services is reduced but also that you are virtually at the mercy of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) because the IMF thrives when countries are in debt. It's very difficult for countries to ignore the policy advice and loan conditions of the IMF when they are in debt. We recently conducted a survey with partner countries of the Global Partnership for Education and found that 25 of these countries are spending more on debt servicing than on education. Therefore, debt has become a major issue. Much of this debt is historical debt, some dating back to the colonial era, some from governments under dictatorships where loans were taken out, and almost no public goods resulted from them. However, the money ends up in tax havens, plundering countries' resources, and the aggressive expansion of debt is the result of events like the war in Ukraine and rising interest rates globally. Therefore, countries that were not in debt until recently now find themselves in chronic debt.

Being subject to the power of the IMF, which is what debt effectively does, is indeed a problem. What the IMF refuses to address is the debt crisis as a collective systemic issue. They only deal with countries one by one to negotiate a solution to a debt crisis. So there is no acknowledgment of systemic causes, and individual negotiations are done in ways that effectively give the IMF complete power to impose austerity policies on finance ministries. It is the austerity policies that drive underfunding of public services worldwide, especially public education. We have seen consistent and projected drops in education spending worldwide over the next three years, primarily due to austerity policies. Specifically, broader public spending constraints have a negative impact on public services. But the most devastating impact comes from restrictions on the public sector payroll and the IMF's insistence that countries cut or freeze their public sector payroll expenses. The two largest groups on the public sector payroll are education workers and healthcare workers. When you are told by the IMF that you need to limit your total payroll expenses, the sectors that suffer the most are education and healthcare. The IMF does not like to give the impression that it is harming education and healthcare, so it claims that it will protect these sectors. However, in practice, this never happens. We have repeatedly shown in research that we collectively published over the past three years with Education and Public Services that the obsession with squeezing the payroll is destroying investment in public services.

One thing we found is that it doesn't matter what percentage of GDP is spent on the public sector payroll at the moment; you are always told to cut it. So Zimbabwe spent 17% of its GDP on the public sector payroll. Ghana spent 8%. Senegal 6%. Brazil 5%. Nepal 4%. Nigeria, only 2% of its GDP went to the public sector payroll. All these countries were instructed to cut or freeze future spending on the public sector payroll. So there is no benchmark that the IMF uses. The only benchmark they use is always recommending a cut or freeze. They cannot provide an academic reference point. Nothing in the literature. Nothing that can justify this, except an ideological belief that public sector spending and the workforce, in particular, must always be treated as a problem. We conducted a study in 15 countries with Education and Public Services that showed that the direct consequence of these IMF squeezes in just these 15 countries was blocking the hiring of 3 million public sector workers. If countries were allowed to increase the percentage of GDP spent on the payroll by just 1%, they could have employed an additional 8 million teachers and healthcare workers. This is absolutely feasible. So there are clear alternatives. The most obvious alternative is, instead of cutting spending, you can increase tax revenue.

In fact, when the IMF's policy unit in Washington was asked to conduct a study to analyze how to finance the Sustainable Development Goals in 2019, the central recommendation was that countries could expand their tax-to-GDP ratio by five percentage points. So the average lower-middle-income country spends about 16% and has a tax-to-GDP ratio of 16%. They could increase it to 21%. Any country that followed this analysis and advice could double its spending on education and healthcare and significantly increase spending on other public services. But we found that, despite this being their own analysis, there is not a single example of the IMF actually recommending this in practice at the national level. They never advise governments to increase tax revenues when giving tax advice. The only advice they seem to offer is to increase the value-added tax (VAT), shifting the tax burden to the poorest sectors of society and, in particular, to women. There are many ways progressive taxes can be increased, taxes targeting the wealthiest individuals and the wealthiest corporations that can absolutely transform education financing. Our most recent research, published two weeks ago, shows that if countries did what the IMF actually recommended in 2019 and increased the tax-to-GDP ratio by five percentage points, they could raise $455 billion for public service investments. If 20% of that went to education, it would be $93 billion for education every year, not as a one-time amount but every year, a massive increase in funding.

Therefore, if countries are genuinely committed to advancing the right to education and education financing and transforming public systems, it's necessary to advocate for tax justice and expand taxes fairly. Currently, we see that all these issues related to taxes, debt, austerity, and payroll constraints are outlined in the call to action of last year's Transformation Education Summit. It is the first time that a UN meeting on education recommends global actions to address the strategic financing issues affecting education. But we haven't seen significant change yet. One of the reasons is the chronic issues around power dynamics that affect what needs to be done regarding the IMF. You have a voting structure in the IMF that was established in 1947, shortly after World War II, before most African countries were independent. And it's fundamentally unchanged. It gives decision-making weight to the wealthiest countries. It's a neocolonial institution. It perpetuates underfunding of public services worldwide to maintain power and create opportunities for multinational corporations, primarily from the Global North. Therefore, this narrative of privatization characteristic of multistakeholderism is based on ensuring ongoing underfunding of public systems when it comes to tax systems. Global tax rules have been set for the past 60 years by the OECD.

The two most famous things the OECD does are setting tax policies and defining assessment systems for education. There, they created a set of global tax rules that allow astonishing levels of aggressive tax avoidance by multinational corporations worldwide, massive illicit financial flows out of countries, and the concentration of money in tax havens. Global rules could have been established long ago to prevent this, but they were not because the interests of the people setting the rules are to keep things unchanged. Last year, a few months ago, the Global Campaign for Education had a global action week called "Investing in a just world: Decolonize education financing now!" referencing this transformative agenda agreed upon at the Transformation Education Summit and attempting to push for changes. We have always been in conflict with education ministries.

We won't change education financing by talking to education ministries. We need to take the argument to finance ministries, heads of state, and global institutions that shape education financing. That's the only way to bring about systemic change.

Therefore, while it's very important to have a strong education movement, what we really need is to unite with other movements.